He was a maverick. In 1908 he published an anonymous article in his modest Urdu journal, Urdū-e-Mu’allā (circulation 500), which severely criticized the British colonial policy in Egypt concerning education. For it the authorities in India charged him with “sedition.” He took sole responsibility for what had appeared in his journal, and spent a little over one year in “Rigorous Imprisonment”-i.e. daily hand-grinding with another “C” class prisoner one maund (37.3 kgs) of grain.

Mohani’s own ghazals should be regarded as some of the best Sufi poetry in Urdu

In 1921 three political groups held their annual meetings at the same time at Ahmedabad. At the meeting of the Khilafat Conference, he succeeded in getting a resolution passed that called for India’s total freedom; but the following day the Conference, not surprisingly, quickly repudiated itself. He next tried his luck in the Subjects Committee of the Indian National Congress; the Mahatma had his resolution voted down. Finally, at the meeting of the All India Muslim League, he made his demand again in his presidential address, but wisely did not risk a vote.

He was perhaps the only prominent Muslim of his generation to publicly champion the radicalism of Balgangadhar Tilak, at whose demise he wrote:

jab tak wo rahe dunyā meN rahā ham sab ke diloN par zor unkā

ab rah ke bahisht meN nizd-i-khudā hūroN pe kareNge rāj Tilak

har hindū kā mazbūt hai jī, Gītā kī ye bāt hai dil pe likhī

ākhir meN jo khud bhī kahā hai yahī, phir āeNge mahrāj Tilak

When he was in this world he ruled the hearts of all of us;

Now in Paradise, nearer to God, he will rule over all the houris.

Every Hindu’s heart is strong, for on it are carved The Gita’s words

And what “he” said himself at the end: Maharaj Tilak shall come again.

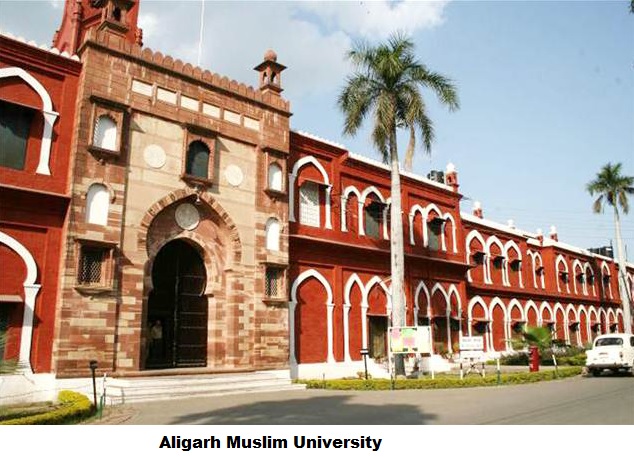

He was born Fazlul Hasan in 1878, in a modest zamindar family of Mohan, a qasbah in Unnao, U.P. After matriculating with distinction when he arrived at the Mahommedan Anglo-Oriental College, Aligarh, in 1899, he got down from the ekka wearing flaring pajamas and his wedding sherwani, and holding a pāndān (“betel-leaf container”) in one hand. The smartly turned-out boys of the college immediately nicknamed him khālajān (aunty). But in short time his personal integrity and his talent for poetry-his takhallus was “Hasrat” (“Longing”)-won him their affection and respect.

After graduation, Hasrat turned his back on the familial property, and chose to earn a living as an editor and publisher while taking part in the ongoing nationalist movement. As a man of letters, he made two enduring contributions: an invaluable multi-volume series, containing selections from the mostly forgotten masters of the Urdu ghazal, and a substantial body of his own ghazals that should be regarded as some of the best Sufi poetry in Urdu. While still in his teens he had been taken by his father to Firangi Mahal in Lucknow to be initiated into the Qadiri silsilah as traced through Shah Abdur Razzaq of Bansa (Barabanki, U.P.). By the time he passed away in 1953, most of South Asia knew him simply as Maulana Hasrat Mohani.

He was a maverick in one more way: he wrote and published verses expressing an intense love for Krishna as an embodiment of Love and Beauty, and probably went to Mathura for Janmashtami as many times as he went to Mecca-by one count 11 times-to perform Hajj.

He was perhaps the only prominent Muslim of his generation to publicly champion the radicalism of Balgangadhar Tilak

Balgangadhar Tilak

Hasrat’s Kulliyāt (collected works) contains a small set of Krishna bhakti poems. Some are in Urdu, while the rest, though written in Urdu script, are in a kind of simplified Awadhi-he called it “Bhasha”-that was prevalent until the Forties among the Muslim gentry of the qasbahs of Awadh, particularly among the ladies, and was often referred to as the kaccī bolī. Fortunately, Hasrat was meticulous in dating his poems, and so we are able to note when and where he first wrote a Krishna Bhakti poem.

Hasrat’s radical speeches at the above-mentioned Ahmedabad conferences soon brought him trouble. He was arrested early in 1922, and remained in the Yeravada Central Jail, Pune, until March 1924. As usual, he wrote much poetry that was published by his wife as separate dīwāns. Glancing through them, one is struck by their extraordinary devotional fervor. They suggest that it must have been a special time in his spiritual life too.

He wrote verses expressing an intense love for Krishna and probably went to Mathura for Janmashtami as many times as he went to Mecca

It was at Pune that he wrote his first poem mentioning Krishna. It is in Urdu, contains only three verses, and bears the date: “September 26-30 [1923].” It is included in his 7th dīwān, which has an interesting introduction. Hasrat writes: “These [32] ghazals were written in just eleven days, between September 20, 1923, and September 30, 1923…. I have occasionally mentioned in them the names of the saintly elders (buzurg) from whom I have received spiritual boons (faiz). In addition to many Islamic personages I have also mentioned Sri Krishna. Concerning Hazrat Srī Krishna ‘Alaihi-Rahma (‘The Revered Sri Krishna, May Blessings be upon him.’), this faqīr follows the path of his pīr and the path of the pīr of all pīrs, Hazrat Sayyad Abdur Razzaq Bansawi, May Allah Bless his Innermost Heart.” He then quotes a verse of his own:

maslak-i-‘ishq hai parastish-i-husn

ham nahīN jānte ‘azāb-o-sawāb

The path of Passion is to worship Beauty;

We don’t care for Reward or Punishment.

The three verses are:

āNkhoN meN nūr-i-jalwa-i-be-kaif-o-kam hai khās

jab se nazar pe unkī nigāh-i-karam hai khās

kuch ham ko bhī ‘atā ho ki ai hazrat-i-Kirishn

iqlīm-i-‘ishq āp ke zer-i-qadam hai khās

Hasrat kī bhī qubūl ho mathurā meN hāzirī

sunte haiN ‘āshiqoN pe tumhārā karam hai khās

When he cast at me an especial, benevolent glance,

My eyes lit up with a boundless, unending vision.

Revered Krishna, bestow something on me too,

For at your feet lies the entire realm of Love.

May you accept Hasrat’s attendance at Mathura-

I hear you are specially kind to all Lovers.

In subsequent weeks, Hasrat wrote several more poems of that nature, all in “Bhasha.”

His first “Bhasha” poem, however, was not about Krishna. Dated October 2, 1923, it praises his Sufi masters in the Qadiri Silsilah, beginning with Shaikh Abdul Qadir Jilani of Baghdad, the head of the Qadiri order, and continuing on, as protocol demanded, to Shah Abdur Razzaq of Bansa (Barabanki, U.P.), whom all the people of Firangi Mahal considered their immediate spiritual master, and Shah Abdul Wahhab of Firangi Mahal, Lucknow, with whom Hasrat had his own direct spiritual link. One immediately notices the vividly ‘feminine’ persona-as distinct from the ‘masculine’ voice in Urdu-that the poet adopts, which suggests that the shift to “Bhasha” from Urdu really reflected a shift or preference in Hasrat’s manner of spiritual devotion. In other words, “Bhasha” allowed Hasrat to relate to his object of devotion-God/Beauty/Truth-in a manner that his heart longed for but found impossible in standard Urdu. Here is that first “Bhasha” poem:

Poem 1. (October 2, 1923; Dīwān 8.)

Baghdādī dayālū khiwayyā

hamhuN garīb han pār jawayyā

birah kī mārī, nipaT dukhiyārī

tākan kab-lag dūr se nayyā

pār utār piyā se mila’o

Razzāk piyā BāNse nagar basayyā

BāNse nagar ke, Firangi Mahal ke

ekai nām ke du’i-du’i khiwayyā

Razzāk Wahāb piyā bin, Hasrat,

hamrī bithā kā kaun sunayyā

Merciful Boatman of Baghdad,

We poor ones too wish to get across.

Separation-wounded, grief-accursed-

How long must we watch the boat from afar?

Our beloved Razzaq, residing in Bansa, please

Take us across; let us meet with the Beloved.

One is from Bansa, the other from Firangi Mahal-

Our two boatmen, who share one name.

Except for beloved Razzaq and Wahhab,

There is no one, Hasrat, who would hear our woes.

He also wrote a second poem that day.

Poem 2. (October 2, 1923; Dīwān 8.)

man to-se prīt lagā’i kanhā’ī

kahu or kī surati ab kāhe ko ā’ī

gokula DhūNDh brindaban DhūNDho

barsāne lag ghūm ke ā’ī

tan man dhan sab wār-ke Hasrat

mathurā nagar cali dhūnī ramā’ī

My heart has fallen in love with Kanhaiya.

Why would it think of anyone else now!

We searched for him in Gokul and Brindaban,

Let’s now go to Barsana and check it out.

Hasrat, give up for him all that is yours

Then go to Mathura and become a jogi.

I have placed here the two poems in the above order on the basis of my understanding of Sufi conventions: Hasrat must have first dedicated a poem to the founding saint of his Qadiri order, Shaikh Abdul Qadir Jilani of Baghdad, and only then turned to praising another personage to whom he was devotionally attached. The first poem traces out his Qadiri lineage; the second focuses exclusively on Krishna. Below are four more “Bhasha” poems from that period.

Poem 3. (October 4, 1923; Dīwān 8.)

mose cheR karat nandlāl

lie Thāre abīr gulāl

DhīTh bha’ī jin kī barjorī

auran par rang Dāl-Dāl

ham-huN jo de’ī lipTā’e-ke Hasrat

sārī ye chalbal nikāl

Nandlal keeps teasing me without end;

There he lurks, ready to pour colors on me.

Having safely sprayed others so many times,

He is now set in his bullying ways.

But what if I should embrace him, Hasrat,

Then squeeze him dry of his fancy tricks?

Poem 4. (October 20, 1923; Dīwān 8.)

birha ki rain kaTe na pahāR

sūnī nagarya paRī ujāR

nirda’i shyām pardes sidhāre

ham dukhiyāran choRchāR

kāhe na Hasrat sab sukh-sampat

taj baiThan ghar mār kiwāR

The unending night of separation lies heavy

Like a mountain; the town is totally desolate.

Heartless Shyam has gone to another land,

Abandoning us, his wretched ones.

Why shouldn’t then Hasrat cast away everything,

And stay home, the doors shut tight?

Poem 5. (October 28, 1923; Dīwān 8.)

puna ho’e na shām kī prīt kā pāp

ko’ū kāhe karat hai pashcātāp

neha ki āg mā tan-man māre

kab lag jalat rahi cup-cāp

dīna-dayāl bha’e dukh-dāyak

sab, hasrat, bhūl ke mel-milāp

Loving Shyam is not a sin, and neither a virtue,

So why do people go on so about Repenting?

How long must I burn in Love’s flames-

Silently, my heart and body suppressed?

He who is “The Wretched Ones’ Solace”

Now gives pain, Hasrat, ignoring all ties.

***

Author’s Note: Excerpted from a longer academic essay in progress. Hasrat Mohani’s collected poems are readily available in Pakistan. People interested in his political life will find the following two books most useful:

1. Ishtiyaq Azhar, Sayyad-al-Ahrār, Bahawalpur: Urdu Academy, 1978.

2. Nafis Ahmad Siddiqui, Hasrat Mohānī aur Inqilāb-i-Āzādī, Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2004.

C. M. Naim is Professor Emeritus of Urdu Studies at the University of Chicago

https://www.thefridaytimes.com/beta3/tft/article.php?issue=20111230&page=24